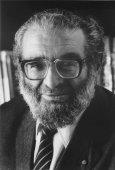

ROBERT

ERNEST DAVIES

|

Born

Melbourne

4 July 1921 |

|

Father

Ernest Davies (deceased 1927) |

|

Mother

Helen Terese (nee Shapira) (deceased 1953) |

|

Siblings

John Dowell |

|

Frances

Alison |

|

Shirley

Helen (deceased 1975) |

* * *** ***

************ *** ******* * ****

EARLY DAYS

Following

the death of our father, the family moved to Daylesford (Vic). It being in the

middle of the so-called Great Depression and in the absence of a Widows Pension,

our mother was obliged to earn a living. She opened a small shop (morning and

afternoon teas and confectionery etc) from which she scratched out a living

while the four kids went to local schools.

In 1930, the

family went back to Melbourne and lived in a succession of rented houses, mostly

in the southern suburbs of Melbourne. Often our stay in a house was of very

short duration, as it was necessary to chase cheaper rental I believe. Both John

(Jack) and I attended Melbourne Boys High School while Frances and Shirley (the

twins) went to Prahran Technical School.

Jack having

matriculated, studied Accountancy part-time whilst working with various firms in

Melbourne. The twins each became Nurses at the Alfred Hospital in Melbourne,

each completing the three year course of training.

AFTER SCHOOL

I

matriculated at the end of what is now known as 11th year, which was the usual

thing in those days. On leaving school I took a job as a Junior Clerk with a

branch of Imperial Chemicals Ltd and stayed with them until the start of the

second World War.

One of the

conditions of employment was that one should study Accountancy part-time so I

started the course with the objective of completing it in five years. However,

after three years, the War started. I was then 18 years of age and could not

enlist for overseas service without the written consent of my Mother so decided

to join the militia for full time service --- this was for service in Australia

only and did not require consent. I spent almost a year in this way and became a

corporal and then a sergeant. It was made clear to me that if I joined for

overseas service, I would be given a commission so went to the appropriate place

and signed up, putting my age up to 21 which meant that my mothers signature

wasn�t needed.

SECOND A.I.F

|

At this stage there was

rapid expansion of the Second AIF and they weren�t being too fussy about

written consent etc. So after a week or two, I was commissioned as a

Lieutenant and put on the fast track for movement to the Middle East, We

travelled in comparative luxury in the 85000 ton Queen

Mary. The next two years saw me in what was then known as Palestine,

Egypt, Syria and the Lebanon. Four months after the Japs entered the war,

our units were shipped back to Australia.

|

|

|

|

I travelled back in a 6000 ton tramp ship and was lucky enough to be

stranded for a month in a small port name Cochin in Southern India because

the ship didn�t have enough coal to get back to Australia. This time our

ship was a little old coal burner from the British-India Line (SS

GARMULA). Top speed 8 knots and only 40 troops aboard. After our coal

arrived, we sailed for Fremantle -- or so we thought. The plan was that we

should be rapidly sent to Darwin as it was thought that the Japs would

invade from that direction. |

After a very

slow voyage back to Australia, mainly due to bad weather, we arrived in

Fremantle to find that we really weren�t expected as wed been so long out of

touch --- the dear old Army more or less thought that wed come to a sticky end.

There was

considerable messing about and changes of plan before the decision was made to

send our Brigade group to Darwin. And there we stayed for about 7 months. There

were a few air raids during that time but none of our crowd were hit.

| During that time I was detached from my own unit and

loaned to an Infantry Brigade Headquarters as a Liaison Officer --- not a

bad job and my own unit was only about twelve miles up the road so I

wasn�t too far away from my mates. Part of my duties as Liaison Officer

meant that I was the contact man between HQ 19th Brigade and a Beaufighter

squadron operating from a field named Coomalleigh

Creek, about 30 miles south of Darwin. One of the flight commanders

was an old school mate (Don Rose) who on finding I�d never been up in an

aircraft decided to rectify the matter. This aircraft had a crew of two

only, so for my illicit flight, I had to go in through the hatch in the

floor then once that was closed, stand on it and hang on to the back of

the pilot�s seat. My several flights were searchlight co-operation

flights over Darwin and the major problem was that there was no way in

which the illegal passenger could be supplied with oxygen if we went above

about 10,000 feet. Don thought this over and told me that if I felt at all

crook, just punch him on the arm --- all very scientific. I survived! |

A 31 Squadron Beaufighter at Coomalie field |

|

At the end of my stay in Darwin, I was sent to the

RAAF School of Army Cooperation in Canberra to spend six weeks learning

how to be an Air Liaison Officer. Quite good really --- 10 Army officers

and 10 pilots all of whom had been in the Middle East. Lectures every

morning then in the afternoons we�d do various training exercises flying

around the general area in Wirraways |

| Then to the Atherton Tableland in North Queensland

where I confidently thought I�d be sent to a job as an Air Liaison

Officer. However that�s not the way the Army works and I was given a

temporary job as Liaison with a new Brigade Group which had been formed to

accommodate the two Militia battalions which had done a fantastic job in

belting the Japs on the Kokoda

Track. Really the purpose of the exercise was to teach them how to put

up with the bulls--t they�d now have to comply with now they were AIF

units. Those guys were real soldiers. In time, of course I had to return

to my parent unit in time to go to New Guinea with them. |

|

|

So--- aboard the troopship DUNTROON and off to the

north coast of New Guinea to scramble down cargo nets hanging down the

side of the ship to get into small barges to be taken ashore. Our Division

was in action in the 100 mile stretch between Aitape

and Wewak with the very tall Torricelli Mountains making life

difficult. However the Army used its loaf for once and I was posted to a

RAAF supply dropping unit as its Liaison Officer. I enjoyed this and used

to fly most days with the �biscuit bombers� assisting with the

navigation. However the fickle finger of fate awaited me!! |

About a year

before this, the British Army asked the Australian Government to let it have

1000 officers of the rank of lieutenant or captain, with jungle experience, to

be discharged from the AIF and re-enlisted in the British Army for service in

Burma. Our people said no way to 1000 but you can have 200. 1 think that at that

time (late 1944) nearly every young officer applied --- including me. As the

months went by, nothing happened except all of us had to front up to War Office

Selection Boards Deafening silence followed.

One night,

down at a place called Cape

Wom where we were actually engaged with the Japs, I received a signal from

our Divisional HQ to make my way back to Aitape and arrange with the RAAF to fly

me back to Australia for early movement to India. I WAS TO MAKE ALL MY OWN

ARRANGEMENTS

There was an

American landing ship unloading stores offshore so I went down and virtually

thumbed a ride back to Aitape and organised with the RAAF to fly me back to

Sydney -- all very unofficial, of course.

During my couple of days

in Aitape, I remembered that my Mother had told me in a letter that one

Lila Rowley was now serving in New Guinea with 2/11 AGH.

|

Enquiries

revealed that 2/11 AGH was in Aitape, so I phoned the SISTERS� Mess and

arranged to meet the lady in question and that evening, visited her in the Mess.

I had met her before the War when both she and my sisters were at the Alfred

Hospital and as a countyi girl she had been invited to our home for a decent

feed as a break from hospital tucker. So I met up with her and in the next few

days made the long air journey Aitape / Merauke / Port Moresby / Cairns /

Charleville / Alice Springs / Adelaide / Sydney / Melbourne. Only the mental

giants who controlled troop movements could tell you why it was such a round

about trip!

Anyway,

needless to say Lila features prominently in this story.

|

|

THE BRITISH ARMY

| The 180 of us who had been selected to go

to the British Army were divided into groups of about 20 and put aboard

various ships --- the war was still on and the Brits didn�t want to lose

the lot of us in the event of the Japs sinking ships.

My group of 20 embarked in Sydney aboard the Royal

Navy aircraft carrier HMS

Begum and sailed to Thursday Island where we picked up some Fleet Air

Arm pilots arid thence to the big British naval base at Trincomalee

in Ceylon (now Sri Lanka). |

The HMS Begum riding at anchor |

We then

commenced a pantomime of amazing proportions! Nobody knew who we were, nobody

knew us and nobody wanted to know us. HMS Begum had to sail so we were put

ashore and were billeted with a Royal Engineer Smoke unit, whose purpose in life

was for someone to press Button B if the Japs turned on an air raid and cover

the naval base with smoke. As the war ended a few days after our arrival, we

didn�t see this performance. However we didn�t escape from the smoke unit

and had to stay with them for about ten days.

Nobody knew

who we were, where we were going. �-not a thing about us.

We started

off on a wandering path --- our needs were simple ---- we just wanted someone to

love us! We went by train to a town in the middle of Ceylon and found that all

towns on this island had a thing called a Guest House where travellers could

stay for a couple of nights and get a bed and a few meals. After that we went to

Colombo where the procedure was repeated. Three days there and then onto another

train to the other side of the island and after bedding down in another Guest

House, we took a ferry to the southernmost tip of India (Talimanar) then by

train to Madras. Another Guest House then train to Calcutta, same again to

Ranchi , again to Lohargarhga, same again to Poona. By now the war had been over

for two and a half months !

|

How

did we live? The British officer is a privileged being and wanderers like

us could obtain a bed and breakfast on request at any Army establishment.

Money??? No problem -- simply go into any branch of the Hong Kong and

Shanghai Bank, produce your ID and get a small advance on your pay. So we

survived. We eventually ran into a reasonably intelligent Colonel in an

officers� mess one day who said he could fix our problem. Which he did

and together with four of my mates we finished up in Poona, of all places.

Eventually the five of us were commissioned into the Northamptonshire

Regiment (the FortyEighth of Foot). The dear old British Army does not

commission people into the ARMY as such, but rather into a specific

Regiment. By this time I had been a Captain in the AIF and the Brits

decided that I should become a Major forthwith.

|

So. I became

a Rifle Company Commander in a Regular British battalion.

Two months

after this the Japs threw in the towel. Either they had learned that Davies,

Batters, Moore, Phillips and Nicholls had arrived in Asia or maybe it had

something to do with the fact that the Yanks had dropped the first atom bomb a

week or so later. Whatever the cause, Japan decided to give the game away. The

War Office decided to send our battalion plus two Scots Regiments to what was

then called Malaya. We travelled from Mumbai (then called Bombay) in great

luxury in a very large ship which had been built for the South American meat

trade. Every part of it was refrigerated and as we were travelling to Singapore

virtually along the Equator. We had a great voyage.

In Singapore

we disembarked, and my Company (A Company) of 105 soldiers travelled in a tiny

clapped out troopship up the east coast of Malaya to a smallish resort town

named Mersing. (any time

you are in our house at Hervey Bay, look in my study and you will see a painting

of the mouth of the Mersing River with all the native huts and boats). A Company

loved Mersing.

We had a bit

less than 1200 Japs to look after as they were now our prisoners. They were

extremely well behaved. The news had now broken about the ill-treatment of the

Australian and English POW�s and I think that our prisoners were determined to

be good boys. We put them on to jobs like cleaning out the gutters in the town,

digging up mines that they had buried in the beach sand (!!) and the more

enterprising of my lads gave them useful jobs to keep them out of mischief.

Several times I went into our soldiers� sleeping quarters to find a Jap

sitting on a charpoy (Indian for bunk) cleaning a soldier�s Bren gun.

A Company

stayed at Mersing while the remainder of the Battalion were located in

Singapore, doing guards of Honour for Admiral Lord Louis Mountbatten or policing

the curfew or generally standing guard at the War Crimes trials.

After three

months we went down to Singapore and joined the rest of the 48th of Foot in

Gillman Barracks which had been built by the Brits just before the war --- very

comfortable. We joined in the Depot Battalion work with the rest of the mob.

We were sent

on a few days leave to a little island (Palang Bakan Mati) in the middle of

Singapore Island which was by way of being a rest camp. (Years later Lila and I

visited this island -- now under its new name � Sentosa -- during a short stop

off in Singapore on our way to Greece.

So we

alternated between garrison work in Singapore, exercises in the beautiful

Cameron Highlands at an altitude of 3000 feet and a spell in Kuala Lumpur.

A DECISION TO BE MADE

About the

end of 1946. we Aussies were invited to apply for regular commissions with the

Brits and while pondering over this I received a letter from Brother Jack to

tell me of a plan the Australian Government had to finance returned soldiers who

had enlisted while under the age of 21 and had served overseas, to do University

courses . GREAT ! One big problem however I had falsified my age on enlistment

and by my AIF records had been older than 21 when I joined up in 1941. However,

back to Melbourne attired in a British Army uniform with all the trimmings, I

went into an Army Records office in Lonsdale St, expecting to get into all sorts

of strife. However--no drama. I approached an elderly Warrant Officer and asked

how did I go about altering my enlistment age. There were so many young blokes

in the same situation that the Army had designed a special form . (�Just fill

in this form and You�ll be right, mate�).

So in spite

of my beautiful uniform, I was in no army at all and was able to go ahead and

apply to Melbourne university to do a Medical course. There were a few hurdles.

Had to go back to school for a year and do Matric. Chemistry, Physics and Maths

at Taylors

Coaching College (aka the Poor Man�s University). So that�s what I did

the year after stopped being a soldier, taking the odd job here and there to

supplement the smallish weekly allowance that the generous people in Canberra

gave us.

A STUDENT

While

waiting to get down to the business of starting my Medical course, there were

certain things to do.

- earn a few pounds. Despite the

tens of thousands being demobilised, there were stacks of jobs. I spent six

months checking invoices at the Commonwealth Dep. of Supply and Shipping in

Melbourne.

- Next Year --off to the Poor

Man�s University (George Taylor & Staff) to study Matric Chemistry and

Physics --- subjects I had not taken at school and which were essential to

get in to the Med. course.

MEDICAL SCHOOL

There were

huge numbers of ex-service people wanting to study Medicine and only three Med.

Schools in Australia (Melbourne. Sydney and Adelaide). With rare genius, the

Melbourne School decided to take over the now disused RAAF Flying School at

Mildura and convert it into a Branch University for first year Medicine,

Dentistry and Engineering. Hangars were converted to lecture theatres and

Laboratories while the troops barracks became two person flats for students. All

first year students were compelled to do their year 450 miles away from home and

all distractions. There was a 50% --50% mix of ex-service people and young

people straight from school. Despite all the gloomy forebodings, this was a

brilliant success and was copied in other parts of the world.

The

Commonwealth Government paid all fees, book costs, rail fares to and from and

board and food. Each student was given five pounds (ten dollars) per week for

general expenses. This was a gift for the first three years after that had to be

repaid. Medicine being a six year course meant a fair size debt on graduation,

Nobody worried at the thought of that. If you failed a year. you were OUT! A

great incentive to study --- if you were tossed out at the end of five years,

you were totally useless!

BUT IN THE MEANTIME�

|

Remember

that Lila Rowley I mentioned earlier? She had now returned from the

Pacific Islands where she was serving in the Army and like so many troops

in those times came back to Australia harboring various tropical diseases

and for quite a while either worked at, or was a patient in, the

Heidelberg Military Hospital.

As a

fairly new civilian, before heading for Mildura, I had been living at

Ivanhoe -just up the road - at my Mother�s home (actually the house

belonged to brother Jack). I think that Lila will be telling you some

important details when she is writing her story. She will doubtless fill

you in on the steps by which two Returned Soldiers decided to get married

on a combined income of about 20 dollars a week and five years study ahead

of me.

|

|

|

We were

married at Christ Church, South Yarra, (where as a school child I sang in the

choir!) on 23 February 1949 and for the first few months lived with my Mother.

With our combined deferred pay from the Army we bought a block of land at

Rosanna 6 miles from Melbourne GPO. Cost us two hundred pounds. Our three

bedroom house was to cost us two thousand pounds !

|

|

No washing

machine (too dear) but the copper could be boiled up when needed. And of course

the copper was most useful on those rare occasions when a crayfish came our way.

Not kind, I know but a great way to get a Cray ready for eating. We didn�t

have a refrigerator either - also too dear. However once each week the ice man

came --- aka Bacteria Bill: he would shove a block of ice into the ice chest.

On the other

hand the grocer would call at the front door one morning each week and later in

the day would deliver the order. We kept chooks in the back yard and collected

the eggs and could eat one every so often but once the chooks were given human

names that little practice lost its charm. We grew our own vegetables, which was

good.

To

supplement our allowance, Lila did some nursing from time to time at the Repat.

Hospital and at other times assisted the pharmacist in the local village. During

University vacations, I�d take jobs -- one time working on the assembly line

building Mickey Mouse radios but mostly working at the Rosella Tomato Soup

factory giving some clerical assistance to the bloke responsible for buying all

the fruit.

Employees

could walk through the factory eating as much fruit as they wanted and could buy

damaged cans of fruit or soup for next to nothing. If there were no damaged

tins, the lads would damned soon damage some for you. No fun, I assure you

carrying a box of a dozen tins of curried spaghetti up the Rosanna Hill to our

house. It wasn�t just the hill -- it was from the factory to the Richmond

station, then change trains at Victoria Park (complete with the dozen cans) ,

get out at Rosanna then up the quite steep hill to the house. Any wonder I

can�t eat curried spaghetti?

|

By now you

will have figured out that we didn�t have a car -- in fact such did not

eventuate until we had been married for five years. A little red Morris Minor

with a fold down hood -- secondhand needless to say, but greatly loved. |

Finally the

time came for my final exams and right in the middle of them, my Mother died

which didn�t help much. This was quite unexpected. Then just before the

Conferring of Degrees, the beautiful Wilson Hall burned to the ground and our

grand ceremonial was transferred to the Union Theatre -- not an impressive

venue, so that was the second disappointment. I asked Lila�s Mother if she

would like to attend in place of my, Mother and to my great pleasure, she said

that she would be honoured. That was on a Saturday afternoon and on the Monday,

I visited the Medical Board and signed the Register and so became a legally

qualified and registered Medical Practitioner. To complete the procedure, I was

then advised that I had been appointed to the Royal Melbourne Hospital which was

exactly what I wanted.

| During my 12

months as an RMO, one of the Senior Physicians (Bill King) asked me was it true

that we wanted to go to country town to practise and advised me to spend the

next year working in a suburban group practice with a boss who could be of great

value rounding off what I�d learned at RMH and the Children�s and Women�s

Hospitals. So the next year was spent working with and under a great man named

Frank Bacon, who not only was an excellent practitioner but also a superb

teacher. Fortunately; the practice was not very far from where we lived so not

too much time was spent in travelling. It was during this twelve month period

that Peter Robert put in an appearance so that when at the end of the year, we

were ready to go bush, we were a family.. |

|

So, at the

start of 1958, four of us arrived in Tongala to take over the practice. (FOUR

??? yes, we took the family cat with us.) I was the only medico in the town --

population about 2500 but with all the ex-service people making up for lost

time, the birth rate was spectacular and I used to preside over the birth of

about 130 babies annually. Car radios had not been invented and the mobile phone

was about 20 years away. Once I went off on a home visit or to a hospital in

another town, Lila was faced with a problem if I was wanted in a hurry for any

reason. However, our phone system was in the pre-automatic era being what was

known as the �wind-and-wait� type. For the doctor�s wife to find out where

the doctor had gone, she�d wind the handle on the antique device and when the

operator replied, ask where the last phone call for the doctor had come from. She

would then phone that number and if I�d left there, the householder would know

where I�d headed for on leaving. Very efficient.

| During the

ten years that we stayed in Tongala (known to the locals as �Tonnie�, of

course) we built a new surgery and a new house and Graeme and Ian arrived to

join the family. We made a number of car trips south to visit both the Rowley

and Davies families. These excursions were made difficult because (a) I always

had to get a locum to mind the shop when I was away and that was never simple

until the Base Hospital at Mooroopna decided to make Resident Medical Officers

available for weekends (at a fee) so that the solo practitioner could get a bit

of a break. Medically they were satisfactory but there were problems ---- we had

one Chinese bloke who used to clean his teeth at the kitchen sink which involved

much spitting (Lila did NOT approve). Another one -- an enormous Italian bloke

--- we booked into the local pub for the weekend where he was notable because at

something over 20 stone, he was so heavy that he broke the toilet seat. |

|

The second

difficulty was that in those far-off days, it was illegal for service stations

to sell petrol between 6pm Friday and 6am Monday which meant having to carry

cans of petrol in the boot with the luggage � not really desirable.

|

We did have

one holiday in a seaside flat at Cronulla in Sydney � big adventure �we flew

from Melbourne in a dear old DC3. The kids enjoyed the beach but Peter became a

bit upset that the prawns and fish were really dead!!! A bit strange for the

keen fisherman he eventually became. |

I still

believe that 10 years in a solo country practice really completes medical

education.

It had its

moments though. We had no Blood Bank of course and if I wanted blood for a

patient they would put it on the evening train from Melbourne which came in at

9.30 pm so when I heard it blow its whistle at the level crossing up the road,

I�d jump into the car and head for the railway station. Before being able to

give the blood to the victim, it was necessary to cross-match the donor blood

and the recipient blood. No lab. closer than Mooroopna and that didn�t operate

at night so I did it myself using a Mickey Mouse device I�d obtained from the

US, fully aware of the fact that if anything went wrong, I�d be crucified by

the Medical Board.

After a few

years, I decided to speed the business up and by now being President of the

local RSL and being much better known, was able to obtain the blood groups of

all the Old Diggers and would call on one or another of them to donate blood for

immediate use -- after my primitive cross-matching ,of course. All of this

business had its lighter moments of course. One night I was confronted by a

woman who needed a transfusion quickly; I consulted the list of donors that I

always carried in my bag and phoned one Kevin Kelly, one of my old soldiers and

told him to come to the local hospital pronto --took a pint from him into a

bottle and immediately transfused the patient before we operated on her. Next

morning, Kevin phoned the hospital and enquired �how�s Mrs X�. The Sister

asked are you a relative to which Kevin replied

�no, I just want to know how she is ----I gave the blood last night and

I�d been on the grog all day and I was afraid she might have a hangover this

morning !!

There�s a

limit to how much of that sort of thing one can stand so we decided 10 years was

enough. Our next move was to Sydney and I�ll tell you more of that when you

reach the section headed �HOMES�.

HOMES

In a way it

is not surprising that we�ve moved around quite a lot and have lived in quite

a number of places since we�ve been married. As Lila has written, she came

from a family that didn�t move away from the Mornington Peninsula. On the

other hand, after the death of my father when I was very young, we lived very

much like gypsies, moving from house to house where the rent was cheaper and

where my mother could eke out a crust, to support her four kids. (Keep in mind

that there was no widow�s pension in those pre World War II days).

So, for a

start, Lila and I shared my mother�s house in Ivanhoe (except it actually

belonged to my brother Jack !)

As service

people, returned from overseas service, we could avail ourselves of a low

interest loan for housing purposes ---- we did this as mentioned earlier, and

had a small house built in Rosanna, about 10 km from the centre of Melbourne,

but actually then the absolute outskirts of the metropolis. And there we stayed

until I had finished my medical course six years later. As we had decided that I

would go into a country practice, about eight years after our marriage, we sold

that house and moved to Tongala (140 miles away) accompanied by our family cat

and Peter who had by this time, put in an appearance. In Tongala, for the first

few years we lived in a house that we rented from the local hospital ---- fairly

basic --- outside toilet which for the first few years was serviced by the

�nightcart man� but after a while the hospital committee decided to install

a septic tank. Some years later, we bought quite a large area on the fringe of

the township and engaged a local builder to build a house designed by an

architect (in retrospect he was a bit of a bushranger). We had farms alongside

and Peter (and Graeme and Ian who had arrived on the scene), could be quite

interested in the cows and calves next door. Television had just come to

Australia in time for the 1956 Olympic Games and we had installed a 130 steel

mast with 30 feet of antennas on the top, with which we could watch the

primitive TV programmes from Melbourne. Tthere was a regional station in

Shepparton (about 60 miles away) but its programmes were lousy.

Anyway, the

TV didn�t matter much because in a severe storm, the mast was blown down and

it almost looked as if an aircraft had landed in the paddock!

The time

came to move on � I think mainly because of the demands of a solo one-man

practice in a country town. It wasn�t tough only for the doctor, as the

doctor�s wife had a hell of a job trying to keep the practice running while

her husband was tearing around the countryside after his patients AND at the

same time looking after three little boys.

From this

�one man town� we moved to Sydney. And what a change that was! We had

managed to sell the Tongala house and now, again with the aid of the War Service

Homes Commission, we bought a house in Rose Bay. Couldn�t see the sea from the

house but from the front gate (with a hit of imagination) you could see a hint

of water.

| One of the

big thrills of that place was the fact the flying boats used to moor on the

water just down the road a bit and every day or so one would take off to fly to

Lord Howe Island. We all learned to sail (after a fashion). Lila, Peter and I

sailed a 16 foot Corsair yacht while the two little boys sailed a 8 foot Manly

Junior ---- with absolutely no success in races, need I say. After a while we

bought a small motor boat and did some exploring of Sydney Harbour. Actually we

did a lot of exploring of Sydney and its surroundings and finished up knowing a

lot more about the Harbour City than a lot of the locals. |

|

|

We had a few

modifications made to the house to make it more suited to our family. The three

boys all went to Cranbrook School which wasn�t far from the house but entailed

a short bus trip which was regarded as a big adventure.

|

|

|

I had gone

completely away from running a practice and took a job as Deputy Medical

Secretary of the Australian Medical Association in New South Wales. To keep my

hand in medically I used to spend every fourth weekend working on the Eastern

Suburbs Emergency Medical Service which covered the King�s Cross area and one

used to see life in the raw. Paid well, however.

In some

respects, it was a bit of a mistake to spend four years in what was virtually a

medical administrative job, however it did broaden my experience of the medical

world in Australia because in country practice in Victoria, I was in many

respects very isolated.

One of the

medical couples with whom I became friendly were on the wrong side of 70 and

after being in rural general practice had gone into the more or less infant

specialty of Occupational Medicine. One day, Naomi --the female member of the

couple- asked me if I�d ever thought of doing likewise and after a few long

discussions with me, told me that the job of Chief Medical Officer at ICI

Australia was coming up and said that she thought I should apply for it. It

would mean a move back to Melbourne but that wouldn�t matter.

I put in a

written application as did a number of other people and after a while was

invited to go to Melbourne where the Head Office was. Met some of the Directors

and had to answer all sorts of questions. About a week later I received a letter

offering me the job and setting out what was the offer.

For a while

I wondered if Naomi had some sort of pull with some of the Directors but

probably they were interested in the fact that I�d been a GP in a farming area

and so was familiar with some of the chemicals being used by the patients.

Whatever the reason we now had yet another house to sell and to up-anchor and

make another interstate move.

| As the new

job was Melbourne-based this meant a move back to Victoria and some changes to

be faced. Our house was about 2 km from the sea and 1 km from the railway. Each

day, the boys went to and from school per bus which picked them up more or less

at the front door. The new school (Brighton Grammar) was not as up-market as

Cranbrook had been for which we were quite grateful. Having been introduced to

Rugby in Sydney, the boys now had to become accustomed to Australian Rules. |

|

A big

advantage was that Sandringham was a convenient starting point on the way to

Rye, where the Rowley family lived, and trips to the Mornington Peninsula were

no longer a rarity.

So before

long our larger family, Lila, Peter, Graeme, Ian, Jason (a little dog) a black

and white cat which answered to various names and a stowaway blue budgie, lived

at 100 Abbott St. Sandringham. As my new job necessitated quite a lot of travel,

I was by way of being something of an intermittent boarder.

My sister

Shirley (another wartime Army nurse) died in her own hospital after a long

illness. Lila�s brother, Des, died far too young, leaving a young family.

Uncle Jack�s wife (Betty --- another nurse) died after a long illness as did

Lila�s sister, Alma. Lila�s father {Grandfather Rowley} had long since left

us, having died before we left Tongala whilst the very small Grandma Rowley

passed on during our stay in Melbourne.

So ---

although life in our new environment had its good points, the extended family

was having its bad times.

Our three

boys were having changes to life style. Graeme joined the Royal Australian Air

Force as an Apprentice Armament Fitter at age 15, which necessitated leaving

home, of course. Peter elected to leave Brighton Grammar and transfer to

Sandringham Tech. and from there to various jobs before buying some land near

Casino in NSW. Where he is at the present time. He gave us our first daughter

when he married Lvnne.

|

Ian stayed

at Brighton Grammar and matriculated there, then proceeding to R.M.I T. where he

obtained a degree in Computer Science. During our last six months or so in

Melbourne, Ian moved to an apartment in Elwood which we had purchased and which

he subsequently bought from us. |

While all of

this was going on. the nature of my job at ICI changed markedly in the area of

Occupational Medicine in the Chemical Industry. My work was now almost entirely

involved in Toxicology ---virtually a new science. A good challenge!! The reason

that it was challenge was simply because at that time there were no courses in

the topic available in Australia and one more or less picked it up by osmosis. I

was fortunate that I now belonged to a world-wide organisation which was able to

put me on the right track.

The timing

was superb because almost coincident with my arrival, the company had to face up

to major problems affecting people in the factory, the field and the

environment.

THE PACIFIC ISLANDS

When I

joined ICI Australia as its Chief Medical Officer in 1970, the job really was

like an Army First Aid post than anything of greater importance. If any of the

hierarchy developed painful haemorrhoids or suchlike, the customary thing was to

get the Company CMO to offer comfort or whatever seemed appropriate.

Actually

this was not in keeping with modern thinking as regards occupational medicine as

it had become to be known. However, times they were achangin� as a popular

song said.

In the

chemical industry, new challenges were cropping up. For example, workers who

manufactured blasting explosives were suddenly found to be liable to have fatal

coronaries on Monday mornings!! But on no other days. Workers who were using a

chemical known as vinyl chloride monomer were found to be developing a very

malignant liver cancer called angiosarcoma of the liver. Why?? People in the

paint industry were found to be dying of curious failure of the respiratory

system. Why??

The

Agricultural Industry was the area where factory workers and field workers alike

were having major health problems and it must be remembered that this was very

soon after the Vietnam War with the memories of Agent Orange etc.

Our parent

Company (Imperial Chemical Industries UK) realised that things were going

haywire and decided that it should tackle the situation head-on. They owned and

operated the world�s largest non-government toxicology research labs, so

decided to bring people like me from all over the world to study these problems.

So in 1970, I went off on a round the world intensive study exercise to meet my

opposite numbers from many different countries.

In passing,

I should point out that this involved leaving Lila with the task of looking

after our three boys for eleven weeks while I was away. Quite apart from

corresponding by letter, we used tape recorders to send spoken messages and this

proved excellent.

My travels

took me to many parts of the USA, to factories and laboratories in England,

Scotland, Wales, Italy, West Germany, France where I met colleagues from

overseas and established very valuable contacts.

No sooner

home than a far greater problem arose.

In

agriculture in most parts of the world, a group of chemicals known as the

bipyridils were being used to kill weeds in crops of all types but especially

sugar. These chemicals (generally known as Paraquat were being known to be

extremely poisonous if swallowed or if skin contact was extreme. Suddenly, in

various parts of the world, it became realised that people were using this

compound for suicide or even worse, to commit murder!

Incidentally,

for no good reason, I have hung on to my passports and find that since my

retirement I have flown out of Australia 29 times. One of these trips was the

grand tour which Lila and I did to Greece, Egypt etc soon after we moved to

Hervey Bay. The other memorable one was late in 1984 (after my retirement) when

the World Health Organisation invited me to attend a two week International

Conference in Geneva to discuss the whole question of Paraquat poisoning. They

kindly offered to pay my air fares and hotel expenses with a side trip to London

after the thing was over.

I should

have smelled a rat when on arrival in Switzerland I discovered that I was to

chair the rotten thing. It was superbly organised with interpreter services and

limousines to take us from the hotel to WHO headquarters each day. I still have

a copy of the 170 page report which I occasionally take a look at as a bit of an

ego trip.

We had the

weekend off and together with a bloke from Nigeria, I took a trip to a place in

the Alps where the very first Winter Olympics had been held (Chamonix).

What did

please me was that we were able to report that occupational exposure to Paraquat

does not pose a risk if there is an adherence to safe working practices.

Armed with

this official opinion, this made my task in the Islands much simpler and really

made it easier to persuade the authorities in the Pacific that we were dealing

with a behavioural problem.

To cut a

long story short, it was up to the Pacific communities to figure out why these

happy people were committing suicide and to find a way to overcome the problem.

So that

ended my difficulties? Like bloody hell! Fiji, Tahiti, the two Samoas etc all

decided to form National Suicide Awareness Committees and invited me to be a

member of each!!!

At least now

I could offer them a treatment for people who had taken a dose, provided the

treatment was started within a few hours but of course this wasn�t always

possible when the patient had to be taken to the only hospital on the island in

question and there were no ambulances or helicopters.

I. was happy

enough to be doing this work from 1983 to 1995 � it was a good interest and

the money was good but what was terrible was that the ICI Brains Trust in the UK

decided to continue the service that I had been doing but replaced me with an

Indian doctor from ICI Malaysia, completely forgetting that Pacific Islanders

� especially in Fiji and Samoa � absolutely hate and loath Indians.

So that was

the end of my long and very happy experience in the Pacific and of course, the

end of the nice cheques that came from London every quarter.

THE ANTARCTIC AND THE ARCTIC

It never did

dawn on me that I might one day see the Antarctic or the Arctic but never, ever

would I see both. Nor that Lila and I would see the Arctic together. Strange

story!

|

When I was

with ICI, the Chief Scientist in the Research Laboratories in Melbourne was a

French/Russian named Grisha Sklovsky. Our work threw us together quite a bit.

One day in 1976 he asked me if I had ever wanted to go to the Antarctic. I

replied that of course I�d like to but so what. End of conversation.

|

|

Some months

later, he told me that his brother-in-law was the chief of Expeditiones Polaires

Francaise --- the French Polar service. Each year he had to organise an exchange

trip to Dumont D�Urville, the French base in Adelie Land. A ship would come

down from Le Havre in France, carrying aboard it a complete change of scientists

to do the next 12 months down there. It would then take the previous year�s

scientists back to France. With two complete parties down there, a problem

existed in that, while the French Army had nothing to do with the operation,

under their law it was compulsory that they have two medical officers on the

Base in case of any medical drama. It had always been their practice to fly a

second doctor out to cover the two weeks when the numbers were up. Grisha was a

very pragmatic character and between he and his brother-in-law they hatched up a

scheme to find an Australian who�d like a nice cold holiday.

|

No pay, of

course, but they would provide necessary equipment and to take care of the legal

side of things, would arrange for the doctor to be appointed Ship�s Surgeon to

the Danish vessel M.V Thala Dan at a salary of 10 francs. All of this was before

the days of video cameras so I took the advice of an RAAF friend of mine who

told me to take a good 8 mm movie camera with me and keep it inside my outer

clothing to stop the works from seizing up. This I did of course, and ran off

reel after reel of film. (Twenty years later after we came to Queensland to

live, I had it all put on to video tape and every now and then, sneak a look at

it.)

|

The

Antarctic is the most photogenic place, what with the penguins, the albatrosses,

the seals, the icebergs and so forth. Lila became quite fascinated by it and we

had thought of taking the (very expensive) one day sightseeing flight from

Christchurch however it was very soon after that Air New Zealand crashed a 747

into Mount Erebos killing all aboard. Sudden change of plan!!

|

Forward

about five years when I was about to make an overseas visit with Lila coming

along too (she used to enjoy the view from the sharp end of the aircraft!). One

of the chores that I had to do was present a paper on Chemical Causes of Cancer,

to be delivered in the beautiful Finlandia Hall in Helsinki. I agreed to do this

on condition that we could then travel to the very north of Finland, above the

Arctic Circle. The organisers agreed so after I�d sung my song in Helsinki, we

flew for two hours up to the very northernmost area of Finland. Not a penguin to

be seen, of course, because they don�t occur in northern Polar regions. A nice

way to spend a long weekend.

|

|

For the

first twelve years of my retirement, ICI (UK) maintained me under contract to

study and deal with certain toxicological problems in Polynesia the arrangement

was delightfully vague in that I was required to visit Samoa, Tonga. New

Zealand, Fiji, Tahiti and PNG at least once each year as appeared necessary to

me. As mentioned, it didn�t take long for me to drop PNG from the list as I

didn�t appreciate the change in the behaviour of many of the indigines.

I soon

figured out a schedule by which I could fit all this into two trips of two weeks

each annually. The highlight of all of this was the visit to Geneva (described

elsewhere).

On my very

last of these excursions, I was accompanied by two very good friends --- both

toxicologists, one Kiwi and one Scot. At the end of our work in Tahiti, I

insisted that we leave Papeete and spend a day on the beautiful island of Moorea

--- surely one of the most beautiful places on the planet. (Lila, Ian and I had

a wonderful holiday at Club Med on Moorea when we were living at Sandringham).

At the end

of 1995, ICI(UK) decided that they would prefer to use a full-time member of

staff on this job rather than an old retired colonial like me. They replaced me

with an Indian medico, quite oblivious to the fact that Polynesians have an

absolute hatred of Indians!!

Great pity

for it to end --- Lila and I had used the loot to visit many parts of Australia

that we wanted to see, such as Cape York Peninsula, Darwin, Perth, the

Kimberley, Central Australia, Kangaroo Island, Monkey

Mia, Tasmania etc.

THE FAMILY GROWS

While the

years were passing. Lila and I had acquired three daughters. We don�t much

like the expression �daughter in law�, much preferring the Samoan style of

welcoming the wives of sons as �daughters�, in this way we have acquired

three daughters. Peter brought Lynne into the family. We have Graeme to thank

for our daughter Sharon, while Susan (Susie) came aboard courtesy of Ian.

While the

years were passing. Lila and I had acquired three daughters. We don�t much

like the expression �daughter in law�, much preferring the Samoan style of

welcoming the wives of sons as �daughters�, in this way we have acquired

three daughters. Peter brought Lynne into the family. We have Graeme to thank

for our daughter Sharon, while Susan (Susie) came aboard courtesy of Ian.

Junior

members arrived too. We have never forgotten dear little Lee who did not survive

and we shared the sadness of this with Peter and Lynne and with Marie and Ian --

the other grandparents. The desperate anxiety of a few years when Simone battled

with leukaemia --- and won the battle-- brought the family much closer together,

and like us, Marie and Ian Hosking will never forget those days and weeks and

months.

Our other

grandchildren give us much pleasure. Melissa and Kimberley now very much young

ladies while the most recent addition -- Juliette with the big dark eyes, just

like her Mum (Susie) is a charmer. We are so lucky to see them quite frequently.

RETIREMENT

We have now

spent almost twenty years in Hervey Bay and the first sixteen of those were full

of unexpected interest. With our radio operator�s certificates that we

acquired before leaving Melbourne, we threw in our lot with H. Bay Air Sea

Rescue (now Volunteer Marine Rescue).

We were both

accepted as radio operators and before long were allocated our own regular

shifts on the radio ---- Lila on Sunday afternoon while I did the Sunday morning

shift. Depending on the weather, this could be either busy or slack. As needs

changed, the number of radio frequencies increased until we reached a maximum of

8, to say nothing of a phone which could he a damned nuisance.

We enjoyed

the job even when genuine dramas cropped up and lives were or might be at risk

or in extreme cases, lives were lost. We remained on the radio job for 15 years

before deciding to retire from it. But that was not the end -- for a number of

years Lila had been the Squadron Contact Person for Critical Stress Management

and finally was elected Patron of the Squadron. (According to the Constitution

of the unit that makes her the Titular Head of the outfit however it�s not an

arduous task other than laying a wreath on Anzac Day, opening building

extensions, attending commissioning of new rescue boats etc).

In addition,

in many instances of real marine urgency, Lila had the experience of being the

radio operator on duty and handled the situations well.

A few years

after we joined the Squadron, I was elected Commodore (which is simply the

marine equivalent of President). I held that job for three years then became the

Hervey Bay representative on the Central Zone Council of Air Sea Rescue

Queensland (Bundaberg, Round Hill, Gladstone and Hervev Bay). A few years later

I was elected to the State Council of Air Sea Rescue Queensland which, soon

after, changed its name to Volunteer Marine Rescue Queensland. In the fullness

of time I became Vice President and later, President, holding each position for

three years.

Perhaps I

should add here that in any volunteer organization, there is a difficulty

getting people to stand for office so all that one has to do is put his head up

and he�s a cert to be elected. Nevertheless there was some satisfaction ---

not in holding the title but in being involved in regular negotiation with the

Queensland Government and visiting most of the 17 Squadrons dotted around the

coast of the State

For the last

three years, our involvement is restricted to attending the AGM and the

Christmas party except of course, for Madam Patron who attends to her duties as

required.

We retain

our membership in the local sub branch of the RSL but have resisted any

temptation to stand for office. Both of us belong to our respective PROBUS

clubs. The word stands for something like Retired Professional and Business

People but really I think it is POOR RETIRED OLD BUGGERS UNFIT FOR SERVICE.

We have

become real Queenslanders but still enjoy watching Aussie Rules football on the

telly but only when the Brisbane Lions are playing.

We have now

(2002) lived in Hervev Bay for just on 20 years and will soon be regarded as

locals. When we arrived here it was rather like seven little fishing villages

with a population of 8500 it is now quite a big city with a population of 43000.

Times do change !!!